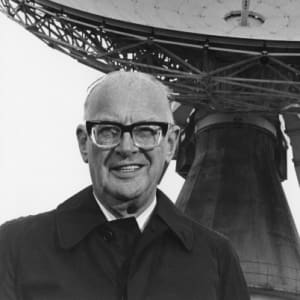

Arthur C. Clarke

An author of nearly 100 books, Arthur C. Clarke’s imagination and insight influenced modern science via works like his classic ‘2001: A Space Odyssey.’

Synopsis

Born on December 16, 1917, in Minehead, England, Arthur C. Clarke established himself as a preeminent science fiction and nonfiction writer during the mid-20th century. He wrote the novels Childhood’s End and 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was adapted into a film with Stanley Kubrick. Clarke authored nearly 100 books, and many of his ideas around science had links to future technological innovations. Clarke died on March 19, 2008, in Sri Lanka.

A Farmer’s Son

Arthur Charles Clarke was born on December 16, 1917, in the coastal town of Minehead in southwestern England. The eldest of four children born into a farming family, Clarke became fascinated with science and astronomy at an early age, scanning the stars with a homemade telescope and filling his head with sci-fi tales from magazines like Astounding Stories.

After his father suddenly passed away, the financial hardships his family endured precluded Clarke from attending university despite his bright, inquisitive mind. After graduating from middle school in nearby Taunton, Clarke left home to find work in 1936.

Early Explorations

Arriving in London, Clarke took on a job as a government bureaucrat. He had not lost his fascination with the stars, however, and he soon became a member of the British Interplanetary Society, which championed the notion of space travel long before it was considered plausible. Clarke contributed articles to the group’s newsletter and also began his first forays into science fiction.

Though these early endeavors were interrupted with the coming of World War II, Clarke’s service during the conflict would present him with the opportunity to indulge his technological aptitude. From 1941 to the war’s end, he was a technician with the Royal Air Force and among the first to use radar information to guide aircraft landings in unfavorable weather conditions.

His wartime experiences would prove fundamental in two of Clarke’s earliest offerings as a writer. In 1945, Wireless World magazine published his article “Extra-Terrestrial Relays,” in which Clarke theorized on how a geostationary satellite system could be used to transmit radio and television signals around the world. This was just the first of many technological realities that Clarke would predict during his prolific career. The following year saw his science-fiction work published for the first time when his short story “Rescue Party” graced the pages of Astounding Science Fiction.

A Man of Many Hats

Returning from the war, Clarke was at last allowed to pursue his higher education after receiving a fellowship to attend King’s College in London. During this time, he also reconnected with the British Interplanetary Society (which he would chair for several years) and continued in his literary endeavors. He graduated in 1948 with honors in math and physics and, straddling the line between scientist and author, quickly set about making a name for himself.

While working as an assistant editor for Science Abstracts magazine, Clarke published the nonfiction book Interplanetary Flight (1950), in which he discussed the possibilities of space travel. In 1951, his first full-length novel, Prelude to Space, was published, followed two years later by the science-fiction works Against the Fall of Night and Childhood’s End (the latter being Clarke’s first true success and eventually adapted into a 2015 TV miniseries). He won his first Hugo Award in 1956 for his short story “The Star.”

Clarke’s writing won him esteem as a novelist and brought him prominence as a revolutionary thinker. He was frequently consulted by members of the scientific community, working with American scientists to help design spacecraft and assisting in the development of satellites for meteorological applications.

Two Frontiers

Amidst all of his extraterrestrial activities, in the mid-1950s Clarke began to develop an interest in undersea worlds. In 1956, he relocated to Sri Lanka, settling first in the coastal town of Unawatuna and later moving to Colombo. Clarke lived in Sri Lanka for the rest of his life and became a skilled scuba diver, photographing regional reefs and even discovering the underwater ruins of an ancient temple. He documented his diving experiences in works such as The Coast of Coral (1956) and The Reefs of Taprobane (1957). He also used his expertise to start the tourism business Underwater Safaris.

Clarke’s destiny, however, was still very much tied to space. After being stricken with polio, which limited his mobility, he turned his attention back to the stars. During the 1960s, Clarke saw some of his most important projects come to fruition. In 1962 he published Profiles of the Future, in which he made predictions about inventions up to the year 2100, and in 1963 the Franklin Institute bestowed him with its Ballantine award for his contributions to satellite technology. That honor was underlined the following year when the Syncom 3 satellite broadcast the Summer Olympics in Japan to the United States.

Space Odysseys

Clarke’s growing reputation as an expert in all things space led to the collaboration for which he is perhaps best known. In 1964, with director Stanley Kubrick, Clarke began work on a screenplay adaption of his 1951 short story “The Sentinel.” It would evolve into the 1968 Kubrick-directed classic 2001: A Space Odyssey, widely considered to be among the greatest movies ever made. Clarke and Kubrick received an Academy Award nomination for their script and also collaborated on developing the story into a novel published the same year. Clarke later followed with the literary sequels 2010: Odyssey Two (published in 1982 and adapted into a 1984 film), 2061: Odyssey Three (1987) and 3001: The Final Odyssey (1997).

At the end of the 1960s, Clarke was able to take part in a real-life space odyssey when he was chosen to join Walter Cronkite as a commentator for CBS’s coverage of the Apollo 11 lunar landing. He returned to the network for coverage of the Apollo 13 and Apollo 15 missions.

Accolades

An internationally renowned author and thinker, Clarke continued his prolific and successful output during the 1970s. His 1973 novel Rendezvous With Rama won both the Nebula and Hugo awards, a feat he repeated several years later with The Fountains of Paradise (1979). In the next decade, Clarke completed the autobiographical works Ascent to Orbit (1984) and Astounding Days (1989). And he branched out into television work once again, appearing as host of the popular series Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World (1981) and Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers (1984) as well as contributing to the Cronkite series Universe (1981).

Towards the end of the decade, polio-related complications further reduced Clarke’s mobility, confining him to a wheelchair. He continued to write works of fiction and nonfiction and garner recognition for his lifetime of contributions. In 1983, the Arthur C. Clarke Foundation was established to promote the use of technology to improve quality of life, particularly in developing countries, through educational grants and awards; and in 1986, the Arthur C. Clarke Award for excellence in British science fiction was established. Clarke also held chancellorships at the University of Moratuwa in Sri Lanka from 1979 to 2002 and the International Space University from 1989 to 2004.

Into the Blue

In the last decade of his life, Arthur C. Clarke was knighted by the British high commissioner in Sri Lanka; was granted that country’s highest civil honor, the Sri Lankabhimanya; and saw the founding of the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Education. He died of respiratory failure on March 19, 2008, at the age of 90. He had written nearly 100 books, along with countless essays and short stories, and made immeasurable contributions to the field of space exploration and science.

In honor of his work, the International Astronomical Union named the distance of approximately 36,000 kilometers above the Earth's equator the Clarke Orbit, and asteroid No. 4923 received the designation “Clarke.”