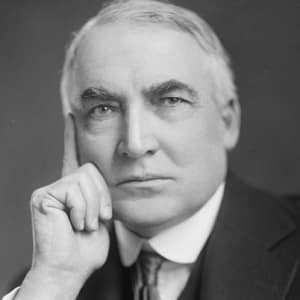

Warren G. Harding

Warren G. Harding was elected the 29th U.S. president on his birthday, and served from 1921 to 1923. His term followed World War I and a campaign promising a “return to normalcy.”

Synopsis

Warren G. Harding, the 29th U.S. president, was born on November 2, 1865, in Corsica (now Blooming Grove), Ohio. Harding's campaign for the presidency promised a "return to normalcy." He was elected president on his birthday and inaugurated in 1921, following World War I. After serving as president for less than three years, on August 2, 1923, Harding died unexpectedly of a heart attack while traveling in California.

Younger Years

Warren G. Harding was born on November 2, 1865, in Corsica, Ohio (now known as Blooming Grove). The son of two doctors, father George and mother Phoebe, Harding had four sisters and a brother. To many, including himself, Harding enjoyed an idyllic American childhood, growing up in a small town, attending a one-room school house, enjoying summers at the local creek and performing in the village band. All of these experiences later helped promote his political career.

At age 14, Harding attended Ohio Central College, where he edited the campus newspaper and became an accomplished public speaker. After graduation in 1882, he taught in a country school and sold insurance. That same year, he and two friends purchased the near defunct Marion Daily Star newspaper in Marion, Ohio. Under Harding's control, the paper struggled for a time, but later prospered, due in part to Harding's good-natured manner and strong sense of community. His 1891 marriage to Florence Kling de Wolfe, a wealthy divorcée with a keen business eye and ample financial resources, also helped the paper to prosper. Harding avoided printing stories critical of others and shared company profits with employees.

Early Political Career

In 1898, at his wife's urging, Warren G. Harding embarked on a political career. That year, he won a seat in the Ohio legislature, and subsequently served two terms. An unwavering conservative Republican with a vibrant speaking voice, Harding did favors for city bosses who, in turn, helped him advance in Ohio politics. In 1903, he became lieutenant governor; and served in that position for two years before returning to the newspaper business.

Though unsuccessful in a run for the governorship in 1910, Harding won election to the U.S. Senate four years later in a hard fought campaign. As senator, he actively supported business interests and advocated for protective tariffs. Like other Republicans at the time, he opposed Woodrow Wilson's "Fourteen Points" peace plan and supported prohibition. Although Harding held strong views on important issues of the time, he didn't often actively participate in the legislative process. According to his congressional voting record, he missed two-thirds of the votes held during his tenure as senator, including the vote on women's suffrage—a cause that he strongly supported.

Presidential Bid

In 1920, political insider and friend Harry Daugherty began to promote Warren G. Harding for the Republican presidential nomination. Daugherty believed that Harding "looked like a president." His upbringing was classically homegrown American. He was well-known by Republican leaders, had no major political enemies, was "right" on all the issues and represented the critically important state of Ohio. At the convention in June 1920, after 10 rounds of voting, the nomination was deadlocked. Finally, on the 11th ballot, Harding emerged as the presidential nominee, with Calvin Coolidge as his running mate.

During the campaign, Harding pledged to return the country to "normalcy." Using clichés in lofty speeches, Harding easily won the election, gaining 61 percent of the popular vote and winning 37 of 48 states in the Electoral College; he was the first sitting senator to be elected president. Opponents James M. Cox and Cox's running mate, Franklin D. Roosevelt, only carried the deeply Democratic southern states.

The Harding Administration

Warren G. Harding's administration was determined to roll back the momentum of progressive legislation that had taken place for the past 20 years. He personally overturned or allowed Congress to reverse many policies of the Wilson Administration, and approved tax cuts on higher incomes and protective tariffs. His administration supported limiting immigration and ending spending controls that had been instituted during World War I.

Harding also signed the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, which allowed the president to submit a unified budget to Congress (in the past, the separate cabinet departments had submitted their own budgets). The act also established the General Accounting Office to audit government expenditures. Additionally, Harding personally championed civil liberties for African Americans, and his administration supported liberalizing farm credit.

In foreign affairs, as in domestic policy, Harding delegated much responsibility to several key cabinet members. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes worked with Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon and Department of Commerce head Herbert Hoover to elevate American banking to a global position; they negotiated trade deals to acquire rubber in Malaya and oil in the Middle East. The Harding Administration also played an important role in rebuilding Europe after WWI, and in establishing an "open door" trading policy in Asia.

As president, Harding often seemed overwhelmed by the burdens of the office. He frequently confided to friends that he wasn't prepared for the presidency. He worked hard and tried to keep his campaign promise of "naming the best man for the job." By awarding high-level positions to political supporters, the results were mixed at best. While Hughes, Mellon and Hoover were very effective, several other high-level appointees—known as the "Ohio Gang"—proved to be unscrupulous and corrupt, paving the way for scandal.

Perhaps the worst disgrace was the Tea Pot Dome Scandal: Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall leased oil-rich lands in Wyoming to companies in return for personal loans. Fall was eventually found guilty of corruption, and was sentenced to prison in 1931. Even Harding's close friend and political manager Harry Daugherty, the attorney general at the time, faced several impeachment votes by Congress and two indictments for defrauding the government. Daugherty was finally forced to resign during the Coolidge Administration.

Privately, Warren G. Harding engaged in the good life emblematic of the 1920s. He and Florence had no children of their own, though Florence had an older son prior to her marriage with Harding. Their social life was made up primarily of elegant garden parties and state dinners. They privately entertained friends at the White House with ample supplies of liquor in violation of Prohibition. Twice a week, Harding played poker with close friends and made the time to enjoy golf, yachting and fishing.

By 1923, rumors of corruption in Harding's administration had begun to surface, and many of his friends were implicated, which greatly disappointed the president. He once commented, "They're the ones that keep me walking the floors at night." That summer, Harding and his wife traveled out west on a political trip to tell people personally about his policies, and to help salvage his reputation. On his return from Alaska, Harding fell ill. His train rushed him to San Francisco, California, where his condition worsened. On August 2, 1923, Harding suffered a massive heart attack and died immediately. In some circles, rumors spread that his wife had poisoned him to prevent him from facing charges of corruption. Her refusal to allow an autopsy only fed the rumors. After a state funeral, Harding's body was entombed at the Marion Cemetery in Marion, Ohio.

Love Affairs

Though rumors circulated while he was in office, it wasn't until after Harding's death that news of his extramarital affairs became public. One of his lovers, Nan Britton, published a book in 1927, claiming that Harding had fathered her daughter while he was a senator. The allegation was a media sensation, and the Britton family was vilified and humiliated in public. Unfortunately for Britton, she had a difficult time proving the affair since she had destroyed Harding's love letters at his request.

In August 2015 new genetic testing revealed that Britton was in fact telling the truth: Her daughter, Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, was the biological child of Harding, ending an almost century-old family feud between the Brittons and the Hardings. “We’re looking at the genetic scene to see if Warren Harding and Nan Britton had a baby together and all these signs are pointing to yes,” said Stephen Baloglu, an executive at Ancestry, to the New York Times. “The technology that we’re using is at a level of specificity that there’s no need to do more DNA testing. This is the definitive answer.”

In 1963, explicit love letters between Harding and a woman named Carrie Phillips were discovered, and revealed that Phillips, a family friend, had engaged in a 15-year long affair with Harding.

Legacy

Most historians consider Warren G. Harding to be one of America's worst presidents. He is believed to have seen the role of president as mainly ceremonial, leaving government work to subordinates. Revisionists have re-examined his role as an important transition between the Progressive Era and the years of prosperity in the 1920s. Harding is also credited for his broad-minded views on race and civil rights. Historians agree that his negative legacy is not so much attributed to his corrupt friends, but his own lack of vision and poor sense of where he wanted to take the country.