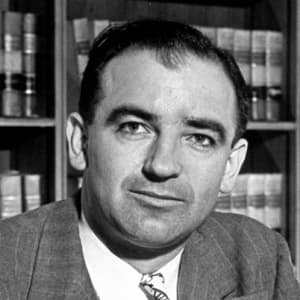

Joseph McCarthy

Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy charged that communists had infiltrated the U.S. State Department. He became chair of the Senate’s subcommittee on investigations.

Synopsis

Joseph McCarthy was born on November 14, 1908, near Appleton, Wisconsin. In 1946 he was elected to the U.S. Senate, and in 1950 he publicly charged that 205 communists had infiltrated the U.S. State Department. Reelected in 1952, he became chair of the Senate's subcommittee on investigations, and for the next two years he investigated various government departments and questioned innumerable witnesses, resulting in what would be known as the Red Scare. A corresponding Lavender Scare was also directed at LGBT federal employees, causing scores of citizens to lose their jobs. After a televised hearing in which he was discredited and condemned by Congress, McCarthy fell out of the spotlight. He died on May 2, 1957.

Early Years and Career

Joseph McCarthy was born on November 14, 1908, near Appleton, Wisconsin. Excelling academically, McCarthy attended Marquette University in Milwaukee, where he was elected president of his law school class. A few years after earning his law degree in 1935, McCarthy ran for the judgeship in Wisconsin’s Tenth Judicial Circuit, a race he worked at relentlessly and won, becoming Wisconsin’s youngest circuit judge ever elected at the age of 30.

McCarthy took a leave of absence in July 1942 and entered WWII as a first lieutenant in the Marines. (He would later lie about being wounded in combat.) McCarthy was still on active duty when he embarked upon his next political campaign: for the Republican nomination to the U.S. Senate. He was defeated but soon began planning for the 1946 Senate race.

U.S. Senate

In 1946, McCarthy won his race in an upset against Senator Robert M. La Follette Jr. and entered the U.S. Congress as the youngest member of the Senate. McCarthy leaned toward conservatism and generally flew under the radar, working on such issues as housing legislation and sugar rationing. All that would change in 1950, when it became suspected that communists had infiltrated the U.S. government in the wake of high-profile espionage trials.

Burdened by an uneventful political career and having an eye towards reelection, McCarthy claimed that 205 communists had infiltrated the U.S. State Department and soon after claimed to have the names of 57 State Department communists, despite having little knowledge of international espionage. As he released his charges, he called for a wide-reaching investigation that would lead to what was termed the Red Scare.

Red Scare

McCarthy was reelected in 1952 and became chairman of the Senate’s Committee on Government Operations, where he occupied the spotlight for two years with his anti-communist investigations and questioning of suspected officials. McCarthy’s charges led to testimony before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, but he was unable to substantiate any of his claims against a single member of any government department.

Despite this setback, McCarthy’s popularity nevertheless continued to rise, as his claims had struck a nerve with an American public tired of the Korean War and concerned with communist activity in China and Eastern Europe. Undaunted by his testimonial shortcomings, McCarthy ratcheted up the rhetoric, going on a colorful anticommunist “crusade” through which he cast himself as an unrelenting patriot and protector of the American ideal. On the other side of the argument, his detractors claimed McCarthy was on a witch hunt and used his power to trample civil liberties and greatly damage the careers of leftists, intellectuals and artists. His aggressive tactics, in the end leading to the persecution and loss of livelihood of countless innocent people, came to be known as McCarthyism.

Lavender Scare

Around the same time as McCarthy implemented his charges around communist infiltration, the senator would also turn his sights to the gay and lesbian communities, alleging that LGBT governmental employees could be blackmailed by enemy agents over their sexuality and thereby betray national secrets. In 1950, a special report drawn up by the senator's Republican allies, the Senate minority at the time, cited gay and lesbian workers as a potential moral threat to the workings of the government.

In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower would sign Executive Order 10450, which sanctioned the administrative policy of tracking down gay-lesbian governmental employees and having them fired due to the labeling of "sexual perversion" as an undesirable trait for employment. Scores of employees were thus fired or resigned out of fear of persecution, with various surveillance measures instituted to try and track down citizens' intimate habits. Frank Kameny, PhD, a gay mapping official and astronomer who was fired from his job, would challenge the order, issue a groundbreaking 1961 legal brief to the Supreme Court (which would deny his petition) and years later organize a protest in front of the White House. Decades passed before the governmental agency ban on LGBT employees was officially lifted by President Bill Clinton.

Televised Hearing

McCarthy's charges of communism and anti-American activity affected more and more powerful people, including President Eisenhower, until 1954 when a nationally televised, 36-day hearing illustrated clearly to the nation that he was overstepping his authority and any ideas of common sense. (The hearings also famously prompted special counsel for the Army Joseph Nye Welch to ask McCarthy, “Have you no sense of decency sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?”) Before the hearings, public opinion had also turned against McCarthy due to a discrediting feature on Edward R. Murrow's program See It Now.

Later Years and Death

McCarthy was eventually stripped of his chairmanship and condemned on the Senate floor (Dec. 2, 1954) for conduct “contrary to Senate traditions.” That turned out to be the final nail in the coffin of the McCarthyism era, and Joseph McCarthy himself fell from the public eye though he continued to serve in Congress. A deeply troubling movement helmed by a demagogue inspired the 1953 Arthur Miller play The Crucible, which looked at the Salem Witch Hunt Trials of the 17th century to draw parallels to contemporary McCarthyism.

McCarthy was historically a heavy drinker and became mired in alcoholism after his fall from public power. McCarthy would eventually suffer from liver failure and on May 2, 1957, died of acute hepatitis at the Bethesda Naval Hospital outside Washington, with his wife, the former Jean Kerr, at his side.