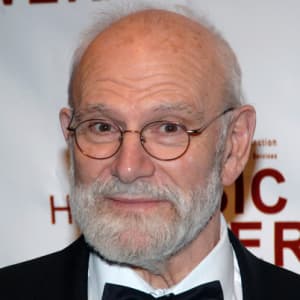

Oliver Sacks

Neurologist and author Oliver Sacks has written numerous works on patients with often unusual conditions. His titles include ‘Awakenings’ and ‘The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.’

Synopsis

Oliver Wolf Sacks was born on July 9, 1933, in London, England. He studied physiology and medicine at Queens College, Oxford. He went on to study neurology and became a professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Sacks has written prolifically about his patients and pathological conditions. His works include Awakenings, Seeing Voices and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. Sacks died from cancer on August 30, 2015 at the age of 82.

A Medical Family

Oliver Wolf Sacks was born in London, England, on July 9, 1933. He was the youngest of four gifted children born into a medical family. His father, Samuel, was a general practitioner, and his mother, Muriel, was one of the first female surgeons in England. After spending his early years at home, Sacks was sent away to boarding school at the age of 6 when World War II began in 1939 to protect him from the frequent bombing raids that plagued London. When Sacks returned home four years later, he attended his local grammar and high schools and developed an interest in both chemistry and medicine, at times assisting his mother with dissections during her research.

Like his siblings before him, Sacks exhibited a keen intellect and excelled in his studies, earning a scholarship to Queen’s College at Oxford University, which he attended beginning in 1951. In 1954 he earned his bachelor’s degree in physiology and biology, and in 1958 received his medical degree from the institution, after which time he interned at a London hospital and worked briefly as a surgeon in Birmingham.

On the Move

In 1960 Sacks took a trip to Canada and while there sent a telegram to his parents informing them of his decision to stay in North America. Hitchhiking his way south, Sacks eventually landed in San Francisco, where he immersed himself in the local scene, experimenting with drugs and befriending some of the city’s local poets. Despite these freewheeling adventures, however, Sacks remained committed to science and gained an internship at Mt. Zion Hospital, followed by a residency in neurology at UCLA. In 1965, Sacks’s career took him across the country to New York City, where he began teaching at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx as well as working at various clinics in the area. It was his experiences during this time that would lead to his first foray into writing.

In the late ’60s, Sacks found a publisher for a book titled Migraine, which described both his own history as a migraine sufferer and the case studies of patients he had encountered during his work at the clinic where he was still employed. Despite the clinic’s objections and its attempts to halt the book’s publication, Migraine was released by Faber in 1970, and Sacks was promptly fired. Though only vaguely successful at the time, the book would establish a formula that Sacks would employ in most of his future writing, fusing clinical observation, the storytelling skills of a novelist or poet and a deeply personal, human empathy rarely found in medical writing.

'Awakenings'

Around the same time that Sacks began teaching at Albert Einstein College, he started working as a consulting neurologist at Beth Abraham Hospital as well. While there he became involved with an unusual group of patients who were suspended in a speechless, motionless, frozen state. Sacks quickly recognized their condition as encephalitis lethargica, the so-called “sleepy sickness,” which had been a worldwide epidemic from 1916 to 1927. Treating the patients with the then-experimental drug L-DOPA, Sacks was able to revive them and relieve them of their symptoms. Their recovery, however, proved only temporary, and the patients soon fell back into their previous state or else developed other similar immobilizing conditions.

In 1973 Sacks published a book about these experiences. Titled Awakenings, it led to a related documentary at the hospital the following year and also inspired the 1982 play A Kind of Alaska, written by Nobel Prize winning playwright Harold Pinter. In 1990, the book became the basis for a critically acclaimed film of the same name, which starred Robin Williams as Oliver Sacks and Robert De Niro as one of the patients. The film was nominated for three Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

The Poet Laureate of Medicine

Once dubbed by The New York Times as the “poet laureate of medicine,” from the 1970s up to the present Sacks has continued to live his “double life” as both scientist and author, documenting his unique medical encounters with a deeply philosophical approach and an often literary flair. In 1985 he published The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, which collected previously published essays on disorders ranging from Tourette’s syndrome to autism to phantom limb syndrome and face blindness, a condition from which Sacks himself suffers. Among his most famous and perhaps most representative works, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat has since been published in more than 20 languages.

INTERESTING FACT: Oliver Sacks suffered from the cognitive disorder prosopagnosia, or face blindness.

Other notable works by Sacks include Seeing Voices (1989), in which he described sign language and its role in the culture of the deaf; An Anthropologist on Mars (1995), which tells the story of seven patients who have learned to adapt to their disabilities; and Musicophilia (2007), in which he discusses cases involving neurological disorders with a musical component. On a more personal level, Sacks published the autobiographical works Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (2001) and Oaxaca Journal (2002).

A Unique Individual

In 2007, Sacks left his position at Beth Abraham Hospital to become professor of neurology and psychiatry at the Columbia University Medical Center. The institution further emphasized its esteem for Sacks when it created for him the new designation of Columbia Artist, which both recognized his achievements transcending art and science and allowed him to teach across a range of departments. While continuing to teach and publish, Sacks has also received numerous honors and awards, including honorary fellowships from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and honorary degrees from Georgetown, Tufts and Oxford, among others. In 2008, he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

“I regard everything I write as being at the intersection of the first and third person, biography and autobiography, as it were.”

In 2010, Sacks published a book titled The Mind’s Eye. In it he discussed various sensory disorders and how patients learned to cope with them. He also described his own experiences with vision loss, resulting from a rare form of ocular cancer for which he had been treated in 2005. Sacks would lay bare his personal world yet again in February 2015, when The New York Times published an editorial by the physician in which he revealed that he had terminal liver cancer related to his earlier eye cancer. Discussing his thoughts on facing his own mortality, Sacks wrote in the article that “When people die, they cannot be replaced. They leave holes that cannot be filled, for it is the fate—the genetic and neural fate—of every human being to be a unique individual, to find his own path, to live his own life, to die his own death.” It is this belief in the uniqueness of the individual that is at the core of Sacks’s empathetic writing about disorders and disabilities. It will no doubt prove to be his greatest legacy.

A new autobiography by Sacks, titled On the Move, was published in April 2015. Sacks continued to write during the final stages of his terminal cancer. In a personal essay titled "Sabbath," published in The New York Times on August 10, he wrote: "And now, weak, short of breath, my once-firm muscles melted away by cancer, I find my thoughts, increasingly, not on the supernatural or spiritual, but on what is meant by living a good and worthwhile life — achieving a sense of peace within oneself. I find my thoughts drifting to the Sabbath, the day of rest, the seventh day of the week, and perhaps the seventh day of one’s life as well, when one can feel that one’s work is done, and one may, in good conscience, rest."

Sacks died at his home in New York City on August 30, 2015. He was 82.