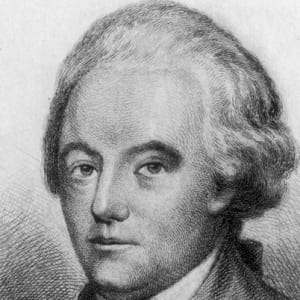

Charles Pinckney

Charles Pinckney was an American founding father, governor of South Carolina and signer of the U.S. Constitution.

Synopsis

Born in South Carolina in 1757, Charles Pinckney fought in the American Revolution and was captured by the British. Upon his release, he practiced law before serving in the Continental Congress from 1784 to 1787, becoming the 37th governor of South Carolina soon after. Pinckney signed the U.S. Constitution and contributed to the Fugitive Slave and "no religious test" clauses. Pinckney later served in Congress, pushing for all white men to have voting rights.

Early Years

Charles Pinckney was born on October 26, 1757, in Charleston, South Carolina. His father was a wealthy planter and lawyer with deep and influential roots in Charleston. Pinckney was taught privately by Dr. David Oliphant, who instilled in Pinckney, among other ideas, the philosophy that if government failed its people, the people had the right to form a new government. This would go a long way toward informing Pinckney's adulthood and eventual role as a founding father of the United States.

When Pinckney "graduated" from Oliphant's tutelage, he studied law under his father and was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1779. (Oliphant's influence also led to Pinckney becoming proficient in five languages.)

The Revolution

When the conflict between the colonies and the British escalated, Pinckney was elected lieutenant in South Carolina's militia (1779). After repulsing advancing troops in Georgia, on May 12, 1780, Pinckney was part of the worst defeat America suffered throughout the war, in Charleston. He and his men were allowed to return home with the promise not to fight, but the British soon pressured him to renounce the patriot cause and join their side. He refused, and as the tide of war began to turn against the British in 1781, Pinckney was incarcerated until an exchange of prisoners secured his freedom.

Post-Revolution

Pinckney began representing South Carolina in the Continental Congress in 1784 (until 1787) and, although he was the youngest member, he played a key role in arranging a national convention to revise and bolster the Articles of Confederation and in calling to strengthen federal authority in raising revenues. He submitted a detailed plan—appropriately called the Pinckney Plan—toward forming a new government, which contained several provisions that became parts of the new Constitution, and his role in determining the general style and content of the document would be hugely important.

He stumped for ratification back in his home state, became South Carolina's governor in 1789 (until 1792, serving again 1796–1798) and guided the state-level implementation of the Constitution in terms of federal–state affairs.

Pinckney began his political career as a Federalist but left for the Jeffersonian Republican Party in 1791, and a year later won a seat in South Carolina's state legislature (1792–1796; 1810–1814). His efforts in getting Jefferson the South Carolina vote tipped the scales in the 1800 presidential election. In 1798, Pinckney was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he served until he resigned in 1801 to become minister to Spain, a post he held until 1804. He ensured Spain's consent to Napoleon's sale of Louisiana to the United States (although he failed to acquire Florida).

Pinckney was an advocate of all white men being allowed to vote but, reflecting his Southern background, was fully against any antislavery provisions in the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

Charles Pinckney died on October 29, 1824, in Charleston.