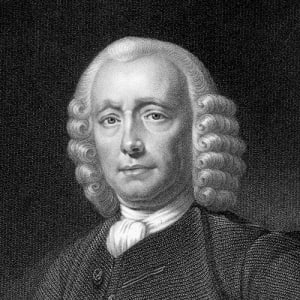

John Harrison

John Harrison was a horologist who is best known for revolutionizing long-distance seafaring in the 18th century by inventing the marine chronometer, which solved the problem of calculating longitude while sailing on the ocean.

Who Was John Harrison?

Born in 1693, John Harrison was an English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer. This device enabled sailors to accurately calculate their ships’ longitude at sea and played an essential role in the development of long-distance seafaring. Harrison spent most of his adult life creating and perfecting his “sea clock,” a solution that eluded other great minds of the day, including Galileo Galilei and Sir Isaac Newton.

The Grasshopper Clock

Harrison often worked with his brother James and one of their first major projects was a turret clock for the stables at Brocklesby Park. This clock proved to be revolutionary. Pendulum clocks of the day used oil to keep the mechanisms moving but they were also the main reason why most clocks failed. Not only are oils subject to changes in temperature that can alter their viscosity, but using too much or too little would also throw off the clock’s inner workings. So Harrison used lignum vitae, a self-lubricating exotic hardwood to construct the escapement, which is the part of the clock that would typically need to be oiled. Eliminating the need for lubrication served as the basis for Harrison’s first sea clock.

How Did John Harrison Solve the Longitude Problem?

In 1714, following several devastating losses of crewmen on ships at sea that were attributed to the inability to calculate longitude, the British government established the Longitude Prize. A reward of £20,000 — several million in today's currency — was to be awarded to the person who could invent a navigational instrument that could find the longitude within 30 miles of a sea voyage.

Astronomers thought the answer lay in mapping out the heavens, but Harrison sought a more practical, mechanical approach. The challenge? For a oceanic voyage starting in England and ending in the West Indies, a marine timekeeper would need to stay within a range of 2.8 seconds per day for a ship to sail within longitude. This was a huge challenge considering the device would need to withstand a range of temperatures and the unstable motion of a ship as well as exposure to storms and heavy winds.

However, sailors could ascertain local time of day at sea by checking the sun’s position in the sky. Harrison believed that if a ship’s crew set sail knowing the time at a fixed reference point and could keep track of it, they would be able to calculate the time difference between that place and their own location. From there, they could determine the distance between the two places in terms of longitude.

The First Marine Chronometer

Harrison began working his first sea clock, or chronometer, in 1728 and completed it in 1735. Called the H1, Harrison’s invention was not only able to maintain the exact time for a long duration, but it could also withstand changes to air pressure and temperature. After doing some test runs on the Humber River, Harrison took his invention to London. It worked well on a test voyage to Portugal, but that was not enough for the board to award the prize, which required use on transatlantic routes.

The Second and Third Marine Chronometers and the Marine Watch

Harrison continued to work on improving his invention’s design, but the H2 and the H3 were not much more successful than the H1. Around 1750, he changed course and began working on a smaller timepiece, the marine watch (H4). Harrison spent six years building it, and was able to prove that this watch could accurately measure longitude. On its first trial to Jamaica, the marine watch proved very accurate — it was only off by five seconds.

However, the Parliament board kept back the full prize and required Harrison to do more trials, although they did dole out money to allow him to keep working. Harrison appealed to King George III to get his full reward and recognition, and the monarch did eventually intervene. In June 1773, an Act of Parliament finally recognized Harrison as having solved the longitude problem, and he received the balance of the £20,000 prize.

Captain James Cook used a copy of H4 on his sea journeys. However, they were expensive to produce, so chronometers didn't become standard instruments on sailing vessels until the mid-1800s when they were considered essential for safer ocean navigation.

Legacy

Before Harrison won the Longitude Prize, the Royal Society, the U.K.'s learned science organization, awarded Harrison the prestigious Copley Medal, the Society's premier award, in 1749. Today the restored H1, H2, H3, and H4 timepieces are on display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. Some of Harrison’s early wooden clocks have also survived and can be found on display at the Nostell Priory in Yorkshire and in London at the Science Museum, which also has the H5 chronometer that he finished in 1770.

Chronometers became vital tools for seafarers and, based on Harrison’s pioneering design, other horologists worked to improve and simplify the devices. Although GPS satellite navigation has eliminated the need for marine chronometers, Harrison’s legacy continues to live on through his inventions.

Harrison’s name made headlines in 2015, when the Guinness World Records announced that a clock built from his design had been proven to be the most accurate swinging pendulum clock in the world. Built in 1975 by horologist Martin Burgess and called “Clock B,” it was taken to the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. Scientists sealed the timekeeper in a clear plastic case for 100 days and determined it had performed accurately, within a second of real time.

Personal Life

Married two times, Harrison had a total of three children. His son, William Harrison, shared his father's passion, assisting him with the development of the chronometer. He later tested the H4 while en route to Jamaica.

How Did John Harrison Die?

Harrison died in London on March 24, 1776; he was buried at St. John’s Church in Hampstead.

Early Life

John Harrison was born on April 3, 1693 (some say March 1693) in Foulby, near Wakefield in West Yorkshire, England and grew up in Barrow, in Lincolnshire. As a child, he contracted smallpox and his parents gave him a watch to play with while he was recovering. This instilled his lifelong fascination with timekeepers — he was soon taking clocks apart and putting them back together to learn how the mechanics worked. His father was a carpenter who taught him the family trade, and Harrison combined those techniques with his self-taught clock-making skills. In fact, he built his first longcase, or grandfather, clock in 1713 with a mechanism made completely from wood.